Daily Current Affairs for UPSC CSE

Topics Covered

- Model Code of conduct

- Electoral Bonds

- Global Hunger Index

- Facts for Prelims

1 . Model Code of conduct

Context: The MCC [Model Code of Conduct] period, which gets extended, has been reduced from 70 days to 57 days by the ECI.

Key Highlights

- The Election Commission (EC) announced that election schedule for Himachal Pradesh Assembly election.

- The Model Code of Conduct] period, which gets extended, has been reduced from 70 days to 57 days by the Chief Election Commissioner.

- The nomination process for the 68-seat Himachal Pradesh Assembly election would begin with the gazette notification on October 17.

- EC had ordered teams to be set up at the district magistrate-level to keep an eye on rumours and fake news spread on social media and take action against the same.

- The EC also issued revised COVID-19 guidelines for States, stating that political parties and candidates must adhere to the rules prescribed by the competent authority.

About Model Code of Conduct

- The Model Code of Conduct (MCC) is a consensus document. In other words, political parties have themselves agreed to keep their conduct during elections in check, and to work within the Code.

- The philosophy behind the MCC is that parties and candidates should show respect for their opponents, criticise their policies and programmes constructively, and not resort to mudslinging and personal attacks.

- The MCC is intended to help the poll campaign maintain high standards of public morality and provide a level playing field for all parties and candidates.

- Adherence to the Code is most important for the government or party in power, because it is they who can skew the level playing field by taking decisions that can help them in the elections.

- At the time of the Lok Sabha elections, both the Union and state governments are covered under the MCC.

How has the MCC evolved over the years?

- Kerala was the first state to adopt a code of conduct for elections.

- In 1960, ahead of the Assembly elections, the state administration prepared a draft code that covered important aspects of electioneering such as processions, political rallies, and speeches.

- The experiment was successful, and the Election Commission decided to emulate Kerala’s example and circulate the draft among all recognised parties and state governments for the Lok Sabha elections of 1962.

- However, it was only in 1974, just before the mid-term general elections, that the EC released a formal Model Code of Conduct. This Code was also circulated during the parliamentary elections of 1977. Until this time, the MCC was meant to guide the conduct of political parties and candidates only. However, on September 12, 1979, at a meeting of all political parties, the Commission was apprised of the misuse of official machinery by parties in power.

- The Commission was told that ruling parties monopolised public spaces, making it difficult for others to hold meetings. There were also examples of the party in power publishing advertisements at the cost of the public exchequer to influence voters. At this meeting, political parties urged the Commission to change the Code.

- EC just before the 1979 Lok Sabha elections, released a revised Model Code with seven parts, with one part devoted to the party in power and what it could and could not do once elections were announced.

- The MCC has been revised on several occasions since then. The last time this happened was in 2014, when the Commission introduced Part VIII on manifestos, pursuant to the directions of the Supreme Court.

- Part I deals with general precepts of good behaviour expected from candidates and political parties.

- Parts II and III focus on public meetings and processions.

- Parts IV and V describe how political parties and candidates should conduct themselves on the day of polling and at the polling booths.

- Part VI is about the authority appointed by the EC to receive complaints on violations of the MCC.

- Part VII is on the party in power.

What is permitted and what is not under the MCC for the party in power?

- The MCC forbids ministers (of state and central governments) from using official machinery for election work and from combining official visits with electioneering.

- Advertisements extolling the work of the incumbent government using public money are to be avoided.

- The government cannot announce any financial grants, promise construction of roads or other facilities, and make any ad hoc appointments in government or public undertaking during the time the Code is in force.

- Ministers cannot enter any polling station or counting centre except in their capacity as a voter or a candidate.

- However, the Commission is conscious that the MCC must not lead to governance grinding to a complete halt. It has clarified that the Code does not stand in the way of ongoing schemes of development work or welfare, relief and rehabilitation measures meant for people suffering from drought, floods, and other natural calamities. However, the EC forbids the use of these works for election propaganda.

- The Election Commission decided that the MCC will also apply to content posted by political parties and candidates on the Internet, including on social media sites.

Is the MCC legally enforceable?

- It is not a legally enforceable document, and the Commission usually uses moral sanction to get political parties and candidates to fall in line.

- Governments have in the past attempted to amend The Representation of the People Act, 1951, to make some violations of the MCC illegal and punishable.

- Although the EC’s stand in the mid-1980s was that Part VII of the MCC (dealing with the party in power) should have statutory backing, it changed its position after the conduct of Lok Sabha elections in the 1990s.

- The EC is now of the opinion that making the Code legally enforceable would be self-defeating because any violation must be responded to quickly — and this will not be possible if the matter goes to court.

2 . Electoral Bonds

Context: The Supreme Court asked the government whether the electoral bonds system reveals the source of money funding political parties even as the Centre maintained that the scheme is “absolutely transparent”.

Key Highlights

- Petitioners said the scheme affected the very idea of free and fair elections provided under Article 324 of the Constitution.

- Petitioners have questioned besides the validity of electoral bonds, whether or not political parties came under the ambit of the RTI Act. The third issue was the challenge to the retrospective amendments made to the FCRA.

- The Centre replied that the methodology of receiving money is absolutely transparent. It is impossible to get any unaccounted money in.

About Electoral Bonds

- Electoral bonds are an instrument through which anyone can donate money to political parties.

- Such bonds, which are sold in multiples of Rs 1,000, Rs 10,000, Rs 1 lakh, Rs 10 lakh, and Rs 1 crore, can be bought from authorised branches of the State Bank of India.

- As such, a donor is required to pay the amount — say Rs 10 lakh — via a cheque or a digital mechanism (cash is not allowed) to the authorised SBI branch.

- There is no limit on the number of electoral bonds that a person or company can purchase.

- The donor can then give this bond (just one, if the denomination chosen is Rs 10 lakh, or 10, if the denomination is Rs 1 lakh) to the party or parties of their choice.

- The political parties can choose to encash such bonds within 15 days of receiving them and fund their electoral expenses. On the face of it, the process ensures that the name of the donor remains anonymous.

- Every party registered under section 29A of the Representation of the Peoples Act, 1951 (43 of 1951) and having secured at least one per cent of the votes polled in the most recent Lok Sabha or State election has been allotted a verified account by the Election Commission of India.

- The bonds go for sale in 10-day windows in the beginning of every quarter, i.e. in January, April, July and October, besides an additional 30-day period specified by the Central Government during Lok Sabha election years.

- The central idea behind the electoral bonds scheme was to bring about transparency in electoral funding in India.

Why have electoral bonds attracted criticism?

- The central criticism of the electoral bonds scheme is that it does the exact opposite of what it was meant to do: bring transparency to election funding.

- Critics argue that the anonymity of electoral bonds is only for the broader public and opposition parties.

- The fact that such bonds are sold via a government-owned bank (SBI) leaves the door open for the government to know exactly who is funding its opponents.

- This, in turn, allows the possibility for the government of the day to either extort money, especially from the big companies, or victimise them for not funding the ruling party — either way providing an unfair advantage to the party in power.

- Critics have noted that more than 75 per cent of all electoral bonds have goes to the ruling party in the centre.

- Further, one of the arguments for introducing electoral bonds was to allow common people to easily fund political parties of their choice but more than 90% of the bonds have been of the highest denomination (Rs 1 crore).

- Moreover, before the electoral bonds scheme was announced, there was a cap on how much a company could donate to a political party: 7.5 per cent of the average net profits of a company in the preceding three years. However, the government amended the Companies Act to remove this limit, opening the doors to unlimited funding by corporate India, critics argue.

3 . Global Hunger Index

Context: India ranks 107 out of 121 countries on the Global Hunger Index in which it fares worse than all countries in South Asia barring war-torn Afghanistan.

About the Global Hunger Index (GHI)

- The Global Hunger Index (GHI) is a tool for comprehensively measuring and tracking hunger at global, regional, and national levels.

- The GHI is jointly published by Concern Worldwide and Welthungerhilfe comprehensively and it measures and tracks hunger at the global, regional, and country levels.

- GHI scores are based on the values of four component indicators –

- Undernourishment

- Child stunting (children under the age of five who have low height for their age, reflecting chronic undernutrition)

- Child wasting (the share of children under age five who have low weight for their height, reflecting acute undernutrition)

- Child mortality (the mortality rate of children under the age of five)

- Countries are divided into five categories of hunger on the basis of their score, which are ‘low’, ‘moderate’, ‘serious’, ‘alarming’ and ‘extremely alarming’.

- According to the methodology, a score less than 9.9 is considered ‘low’, 10-19.9 is ‘moderate’, 20-34.9 is ‘serious’, 35-49.9 is ‘alarming’, and above 50 is ‘extremely alarming’.

- Based on the values of the four indicators, a GHI score is calculated on a 100-point scale reflecting the severity of hunger, where zero is the best score (no hunger) and 100 is the worst.

Findings of the Index

- The hunger score of the world is currently at 18.2, which has been only slightly lower than the 2014 score of 19.1. South Asia remains the region with the highest levels of hunger and with the most concerning issues pertaining to child nutrition.

- As many as 17 countries have been collectively ranked between 1 and 17 with a score of less than five.

- The list, which ranks Yemen in the lowest position at 121, has 17 collective top-ranking nations — the differences in their severity scoring is minimal.

- China and Kuwait are the Asian countries that are ranked at the top of the list, which is dominated by European nations including Croatia, Estonia, and Montenegro.

- Though the GHI is an annual report, the rankings are not comparable across different years.

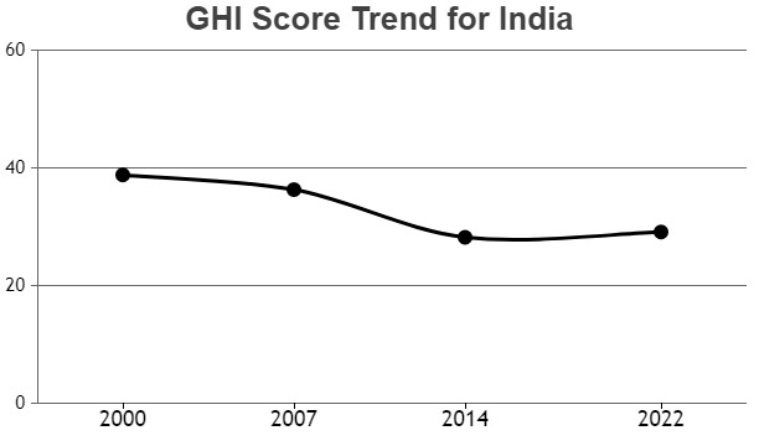

- The GHI score for 2022 can only be compared with scores for 2000, 2007 and 2014.

Performance of India

- India’s score of 29.1 places it in the ‘serious’ category.

- India also ranks below Sri Lanka (64), Nepal (81), Bangladesh (84), and Pakistan (99).

- Afghanistan (109) is the only country in South Asia that performs worse than India on the index.

- India has been recording decreasing GHI scores over the years.

- In 2000, it recorded an ‘alarming’ score of 38.8, which reduced to 28.2 by 2014.

- The country has started recording higher scores since then.

- India’s child wasting rate (low weight for height), at 19.3%, is worse than the levels recorded in 2014 (15.1%) and even 2000 (17.15) and is the highest for any country in the world and drives up the region’s average owing to India’s large population.

- Prevalence of undernourishment, which is a measure of the proportion of the population facing chronic deficiency of dietary energy intake, has also risen in the country from 14.6% in 2018-2020 to 16.3% in 2019-2021.

- This translates into 224.3 million people in India considered undernourished.

- But India has shown improvement in child stunting, which has declined from 38.7% to 35.5% between 2014 and 2022, as well as child mortality which has also dropped from 4.6% to 3.3% in the same comparative period.

- On the whole, India has shown a slight worsening with its GHI score increasing from 28.2 in 2014 to 29.1 in 2022.

4 . Facts for Prelims

INS Arihant

- Launched in 2009 and commissioned in 2016, INS Arihant is India’s first indigenous nuclear powered ballistic missile capable submarine built under the secretive Advanced Technology Vessel (ATV) project, which was initiated in the 1990s.

- INS Arihant and its class of submarines are classified as ‘SSBN’, which is the hull classification symbol for nuclear powered ballistic missile carrying submarines.

- While the Navy operates the vessel, the operations of the SLBMs from the SSBN are under the purview of India’s Strategic Forces Command, which is part of India’s Nuclear Command Authority.

- In November 2019, after INS Arihant completed its first deterrence patrol, the government announced the establishment of India’s “survivable nuclear triad” — the capability of launching nuclear strikes from land, air and sea platforms.